Fifty years ago, July 27, 1963, a family was lost.

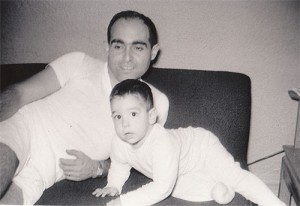

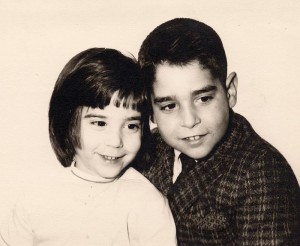

The Lerner family consisted of a vibrant, playful mother; a confident and charismatic father; a six-year-old girl who was already filled with a love of music and performing for an audience; and a ten-year-old boy—the beloved firstborn son, the bright if sometimes hard-to-teach student, the prankster but loving older brother, the leader of his generation of cousins, the rough-and-tumble athlete.

The foursome lived in East Meadow, a Long Island town that was home to families who weren’t wealthy but were certainly more comfortable than their parents had been. The mother and father’s parents were all immigrant Jews who had known dire conditions both in American and in their various native Eastern European homes. But the mother and father were 1st generation Americans, married in 1950 right in the center of the 20th century, where enough work, talent and hope allegedly guaranteed you a prosperous and gilded future.

The Lerners were on track to fulfill this promise. Home movies from this time show softball games, picnics, the daughter dancing and pirouetting and preening for the camera, the mother smiling with pride and love, the father pulling amusing faces and coaching the various games, the boy running and playing and laughing because he was happy and healthy and likely felt as immortal as most loved, cared-for, and care-free children do.

Two days before this Lerner family ended, the father—my father, Morty, 41 at the time—was standing outside in his yard, the family probably having finished celebrating his wife’s birthday (this would be my mom Shirley, 36). The summer twilight was likely full of typical sights and sounds. Cicadas, fireflies, maybe other families in their yards with barbeques. But he was paying attention to his children playing in the family’s above-ground pool, that symbol of upwardly-mobile parents throughout suburbia.

As he told me many years later, at this moment he thought to himself—with what I consider understandable pride of accomplishment for someone whose father had a rag-picking business, but what Pop later considered unbearable hubris: Look at them, he reflected as he looked at son Kenny and daughter Karen. Look at how much they’re enjoying themselves. Thank God I was able to give them this kind of happiness.

Less than 48 hours after this quiet, content moment, Morty received a call at work to hurry home. Nothing else, just—hurry home. He must have demanded at least some information, but the friend who called gave him only the starkest detail: There’s been an accident.

When he arrived, he would have found a nightmare in broad daylight. Police. Neighbors. His wife inconsolable. His daughter likely scared and confused. And his son…

His son was dead.

And with this knowledge, which made him the final member of the family to learn of this inconceivable tragedy, the destruction of the happy Lerner family was complete.

The circumstances of the death are painful to describe. It was a freak accident, the kind no parent wants to think about. A few moments of lapsed attention on my mother’s part, her asking Kenny to watch his sister while she ran inside for a few minutes—I don’t know why; laundry, a phone call, an oven timer? It’s hard for me to comprehend anything that would have torn my mother from watching her kids—I knew her as an incredibly eagle-eyed woman, overprotective to the point of neurosis. But then again, that was a Shirley Lerner post-July 27, 1963.

Mom knew Kenny was a skilled swimmer and Karen was probably glued to the side of the shallow pool, so what harm could there be in dashing away for such a short period of time?

When she left, Kenny began swimming underwater and playing games near the pool’s ladder. My sister Karen, so achingly young, stayed where she was told near the edge of the pool. Then Kenny didn’t come back up. He was kicking. Little Karen grew upset, yelled at him to stop scaring her. Her cries met my mother as she ran back outside. Already too late.

Mom had to jump into the pool, disentangle her son from the ladder, and drag his body to the lawn. Somehow she got Karen out of the pool too, told her to stay with Kenny—Karen dutifully held her brother’s lifeless head as ordered—while her hysterical mother proceeded to run through the neighborhood in search of help. Neighbors reported to the police that my mother kept screaming “My son is dead!” So she already knew it was hopeless. But she still ran for help anyway.

I call this family lost because the original Lerner family did die that day. Mom, Pop and Karen continued to live, thank God, but they would never be the same family again.

Seven months later, Mom was pregnant with another child, and in November 1964 gave birth to another daughter, “her savior” as she’d once call my sister Kim. Having another child was probably advised from many quarters, a way to show that life continued, a way to give Karen another sibling, and a distraction from my mother’s ceaseless self-recriminations.

Of course, there was a 7 1/2-year difference between Kim and Karen. Karen would be off in college by the time Kim was only ten. That wouldn’t be fair. So, after another nineteen months, another daughter was born. No one’s savior, but a companion for Kim: yours truly.

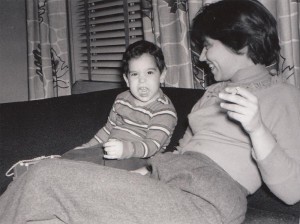

My mother and me when I was ill as a baby. Her fear and sadness are written on her face.

The carefree Lerner family? I never knew them. As I said, my mother was overprotective and gimlet-eyed when it came to Kim and me. (And to others’ children, as well; she would insist on driving our friends home from playing at our house even when their parents didn’t mind them walking home alone.) Even when I was 11, I couldn’t so much as take a bath without singing loudly to prove to my mom I was okay. While I was growing up, Mom stuck to herself, stayed home much of the time, played endless rounds of solitaire or read books. Admittedly, according to her brother (my uncle Danny), as a girl Mom had always been content to be alone. But I look back and know she wasn’t content. She took little care of herself. Her health, even her hygiene, all suffered from lack of attention.

As my father said during one visit to her grave in the late 1990s: “She just couldn’t forgive herself. Nothing I said or did seemed to help. She just couldn’t forgive herself.”

Mom had moments where she could enjoy herself, of course. She delighted in her three daughters’ talents in music. She could, now and then, still go out to “the city” to meet Pop for dinner and a show or a basketball game. She was an avid Anglophile and in 1972 we spent a happy summer in England, which allowed her to drink in as many historical and literary landmarks as she could.

Her abilities to drag herself out of the house waxed and waned over the years. Sometimes she could muster up the energy; most times she couldn’t. Depression and guilt gripped her and in many ways she had branded herself as someone who not only didn’t deserve the pleasure, but someone who was justifiably doomed not to have it.

My father’s attempts to lift her spirits waxed and waned too. He wasn’t a saint and lacked the patience of one. He spent much of his time trying to keep his businesses afloat, working late into the night.

We lived in a much more affluent community now—my parents had moved from their old home five years after the accident. Frankly I’m astonished they were able to wait even that long to flee the scene of the tragedy, but I can only assume that they simply lacked either the money or the willingness to uproot Karen from her school. Perhaps there was even a subconscious reluctance to leave the home where their son had last lived.

So we had moved to Great Neck in 1968, living in a beautiful Tudor home with exorbitant taxes thanks in large part to the excellent school system, one of the best in the country. But honestly, my family couldn’t afford to live there, not really. We were slaves to that house and the taxes. On the outside we matched the other families in Great Neck, but inside the house it, and we, were barely holding ourselves together. The pressure on my father was enormous, and Mom would’ve been supportive but, being so low in energy herself, she surely wasn’t able to help him escape his own flailing psyche.

He had guilt too, you see. He’d bought the pool. He couldn’t fix his son. He couldn’t fix his wife. He couldn’t maintain both his companies—one went bankrupt, putting no end of fiscal stress on him until the day he died. When he’d come home from work, the house was usually messy, my mother not having the wherewithal to keep things neat, and not having the desire to discipline her children into helping with chores. So every weekend meant dreading my father’s fed-up reactions. In retrospect, his anger over disorder was so obviously misplaced anger at a chaotic household, a depressed wife, and what he saw as his own failures as a provider of money and safekeeping.

Karen grew up placed in an awkward position in the family: forced to grow up too young, feeling guilty for having survived, she was both one of the three Lerner daughters and also part of a different triad: the survivors of the unspeakable tragedy.

The Big Golden Book that revealed more than one story. Kenny’s signature is on the inside cover. Click to enlarge.

Karen was treated as a partner of my parents, not one of the “kids” (as Kim and I were called). She was part of this secrecy, though I doubt it was ever a direct command in so many words. But even after I knew about Kenny too, I joined the conspiracy of silence as well. We all knew the rule: do not mention Kenny.

Kenny’s loss radiated outward in many ways as well; my aunts, uncles, cousins… all of them experienced this tragedy and had their own reactions to it. I know less about their lives, but it must have devastated them, especially those who were closest to him and my parents.

Going back to the secrecy… it’s astounding that despite not knowing of his existence, much less his death, I still knew on a subconscious level that something was wrong with my family. I knew we were different, I just didn’t understand how or why. I certainly knew I was different. I was scared of everything. The reason for this is pretty easy to figure out. My mother had such a terror of anything happening to her children ever again that if she could’ve enveloped us in bubble-wrap for the entirety of our childhoods, she’d certainly have done so. She warned me about everything: don’t put your head under the water. Don’t run too fast. Don’t jump on the couch. Don’t stand on your head. Don’t cross the street. The underlying message was: Don’t risk anything… or some dire consequence will result.

I grew up waiting for those dire consequences. I inherited her fears and embraced them, and she indulged me in them as well. If something was too hard for me, I was allowed to forgo it. This may have allayed my fears temporarily and made my mother more comfortable, but the end results of such avoidance were never good. I was too afraid to go to nursery school, and she let me stay home. So when I finally was forced into kindergarten, I had no experience of playing with other kids except my sister Kim and her friends. I couldn’t make my own friends. I didn’t understand why all the others seemed to know each other. (Probably because they’d been to nursery school together, of course.) I couldn’t talk to strangers and felt awkward and stupid and shy and ugly. In those days parents didn’t make “play dates” for their children, so I went home by myself and learned to play with my dolls or stuffed animals, and let these friends make up for those I couldn’t construct out of my imagination.

Even once I knew about Kenny, there were still lies. Apparently, Kenny didn’t drown. He was hit by a car. At least that was the official story my mother told me and I believed for two years (why wouldn’t I?). Until the night when I was taking a bath and didn’t follow the rule I mentioned earlier, the one about making lots of noise. I was about 12 and doing something silly, probably just splashing around with my dolls (I played with dolls way later than most kids did, or do; as I said, they were my friends and I didn’t give them up easily). I guess I was too quiet for too long, because suddenly my mother burst her way into the bathroom as if the house was on fire. She then yelled at me for not singing or whatever. Shaken and indignant, I asked her what was the big deal, why did she have to scare me like that? And with a look on her face I will never forget, she pinned me with her glaring, nearly black eyes and blurted: “My son drowned!” As I stared at her, she seemed unable to say anything else. She just turned and left me. I sat there in the bath, letting the water drain out, in utter shock. Confused. Embarrassed. And above all, horrified at having upset my mother–the worst sin of all.

The conspiracy that kept my brother’s very life an unmentionable thing, this rule of do not upset your mother, do not talk about Kenny, was so ingrained–on, like, a DNA level–that I didn’t do what I think most kids would have done: go into my mom’s room and ask her what she meant. (In fairness, my mother never approached me either, and as an adult I think it was her responsibility to do so.) Instead, once I dried off and got into my pajamas, I went into Kim’s room and asked her what Mom had meant. Kim, of course, already knew the truth, and so she was the one to explain that the whole car-accident thing was fiction. Supposedly the reason was that my mother didn’t want me to be afraid of swimming. (Which is almost amusing, considering that Mom had already made me terrified of swimming simply by osmosis—her own fear was so great there was no way I wouldn’t be infected by it.)

But years of therapy and simply being a psychologically aware adult have made me suspect that the reason that a real drowning turned into a fictional car accident tale was that Mom didn’t want to answer the questions that would have followed that revelation—above all, the one she would never have had a good enough answer for: Where were you, Mommy? This alternate version had many benefits. A car accident was random, unpredictable, and above all, someone else’s fault. A boy drowning in a pool when his mother should’ve been watching him? How could she have explained that to me? How could she have admitted that she wasn’t all-seeing, wasn’t able to protect her children?

So we were a sad family, a dark family. I grew up knowing my parents were often unhappy but never understood why. Once I finally did learn that why, the fact that I couldn’t talk about it with anyone led me to think all sorts of things. Some of them untrue, but one thing certainly was. I would never have been born if Kenny hadn’t died.

I’ll put it another way: I owe my life to the fact that my brother drowned.

This isn’t a melodramatic declaration. It’s simple math and knowledge of how our family would likely have been constituted, knowing our culture and the sizes of my relatives’ families. No one has four children in our extended family. It’s vanishingly unlikely that my parents would have had two kids in the ‘50s, then repeat the process nearly eight and nine 1/2 years after.

I knew I was basically a back-up, someone whose life was dependent on a terrible accident that devastated her parents. That understanding, that guilt, so took hold of me that I vividly remember one day when I started to think: it was him or me. As if there had been some kind of duel in Heaven (not that I’m religious, but work with me here…) and I’d had to kill my brother in order to be born.

Having this grim thought, and knowing Kenny mostly through the hagiographic memories that are entirely understandable when talking about a little boy who died, I soon became convinced of one thing: the wrong person won that duel.

I wasn’t worth the loss my parents suffered. I had ugly thoughts, I was angry, I wasn’t good in school, I wasn’t athletic, I was lazy and cripplingly shy. Worse, I was clearly not likeable since I had no friends (well, I had one friend, but I was so insecure in that friendship that I would constantly try to bribe my way into her heart by buying stuff for her).

I remember throwing a party in the 2nd grade and inviting just four girls: Amy, Gail, Michelle and Sloane. I waited in the driveway for them to show up. It took a half hour and only Sloane appeared. Turned out the other three just ditched me and went to one of their houses to play. I learned the lesson pretty quickly to stop making overtures to others. I mean, there was obviously something so fundamentally flawed and unattractive in me that not even the promise of cake and party favors could outweigh the negatives of my deficient personality.

So why was I alive? Why would God or whatever take Kenny away and put this person in his place?

I’ll be honest with you: I still don’t have the answer to that question. I know better now than to think there was some Battle Supreme in which the wrong person won. But I still have never been able to shake the feeling that I’m just… wrong. Malformed. A mistake.

* * *

I recently watched an episode of a TV drama called Switched at Birth, which is based on the premise… well, you can probably figure it out, the title says it all. In this episode, the writers chose to view an alternate reality: what if the truth about the baby-swap had been discovered earlier?

Coming so closely to the 50th anniversary of my brother’s death, this episode invariably made me think, for the first time if you can believe it, of my own alternate reality scenario: What if Kenneth Michael Lerner had never drowned?

That original foursome Lerner family would have remained intact. Kenny died too young for me to know much about what his aspirations might have been, but knowing my family’s artistic bent, he might have gone into acting or performing; the rest of us certainly did. He’d probably have played lots of sports, too, and would have remained very close to his cousin Bill, as well as his other cousin Richard. Of course, I wonder if he’d have gone to Vietnam. He would’ve been 21 in 1973. I’m not sure if a likely college-bound kid would have ended up being drafted. (I know embarrassingly little about how the draft worked.) I certainly hope he’d have missed the war. Assuming he did, or that he came back healthy and unharmed—and since he’d likely have been a good-looking young man (my father was handsome and my mother beautiful)—he may well have chosen a career in performing or, if he took after my father’s own one-time ambitions, sports broadcasting. By 2013, he’d be—it’s unfathomable to realize this—61. A grandfather, possibly.

Karen wouldn’t have grown up laden with survivor’s guilt and anger and a need to take on responsibilities that weren’t her own (she was considered the “adult” of the daughters way too young). She would have had an older brother to look out for her, and maybe she wouldn’t have had such a hard time in high school. Maybe she’d have had more confidence to follow her dream of being a concert pianist. In this reality who knows exactly when or whom Karen might have married and had a family—I only hope it would still have been my lovely brother-in-law Richard and amazing niece Katie. If so, Katie would have been blessed with had an energetic uncle rather than the depressive aunts she’s been stuck with.

My mother… she’s especially hard to imagine in this alt.Lerner family. I can only assume she’d have had far fewer fears, and none of the crippling guilt or depression. She might have been able to indulge her love of singing and theater once Kenny and Karen were older. With her husband she’d have gone on more trips, spent more time at concerts and the theater, going dancing, being vivacious and loving with each other. Once Karen went to college in the mid-1970s, they’d have been able to go on so many wonderful excursions with each other. She would have remained a mother hen to her nieces and nephews, a cherished older sibling to her sister and brother. I have to believe she’d have taken better care of herself. Whether that would have meant stopping smoking—which caused the cancer that killed her at 59—I have no idea. Maybe she would still have died painfully young. But it would have been after a much richer, happier life. Not that this makes such an untimely death more palatable, but it certainly would have made memories of her less filled with regret and unfulfilled dreams. And if she had somehow managed to survive, she’d have lived to see her children married and with kids of their own. My mother as a grandparent would have been incredible. I look at Katie and imagine how much my Mom would have adored her, and it makes me weep.

Pop might have been the least changed in this reality, primarily because he would still have worked too much. But with his son alive, he wouldn’t have been driven by a gnawing sense of guilt, and he wouldn’t have been at a loss to help his wife recover from something unrecoverable. I can easily guess that he and Kenny would’ve have had some rocky times over the years, what with Pop being so hard on himself and possibly projecting that even more onto his son than he did with his daughters. But I can’t imagine Pop being anything but over-the-moon proud of whatever Kenny became. And if by some miracle Mom hadn’t died so young, leaving him a widower, they’d have had many, many years of happiness.

Kim and I… well, if this were a television episode, the actors portraying us would have the week off. We wouldn’t exist. I suppose there’s the barest possibility that a version of Kim might have been around, as three kids wouldn’t have been unusual for a family in that era. (Four would have been right out, though; not for Jewish, upwardly mobile families. Too many children was a sign of poverty and poor planning.)

Not having Kim would be a big loss for her friends and her clients. And for her dear husband Matthew. My mom would’ve missed out on having a singer for a daughter, and that would have been a disappointment for her; she adored having an opera singer in the family and I know she got lots of pleasure from that. Depending on Kenny’s political bent, Pop would certainly have missed out on a child whose ideals were as closely aligned as his and Kim’s were.

Without me… I don’t know. I don’t see my absence as making that much of a dent in the world. I don’t really bring that much to it. I suppose my friend Leslie might have had a slightly different sensibility regarding comedy and so on, but otherwise I think I slip out of this hypothetical TV show cast pretty easily.

But that’s all this is. A hypothetical. Kenny’s life is a half-century away, and the Lerner family lived its often somber yet loving (despite the sadness, the love we had for each other was very real) existence without him, with all of us permanently damaged in one way or another—even those of us like me and Kim, who never knew him.

There is one final alternate reality I wonder about—the least likely one, the one where Kenny is alive and so am I. How would I feel having a big brother, fourteen years my senior? It took quite some time for Karen and me to forge a relationship despite our 9-year-difference, as she was away in college or graduate school for most of my “sentient” early years (8 – 14). Would Kenny and I have grown close too? Would I have been more comfortable around guys as a young woman if I’d had a brother? Would I have felt safer? I’d certainly have felt less guilty and depressed, since the household I grew up in would have been completely different. Would we have been alike in any way? Would we share interests? Would I still feel so damaged? Maybe it’s too easy to blame my flaws on the tragedy that consumed my family. Maybe I would still battle self-loathing and depression. Or maybe I’d know happiness and contentment, two states that in real life will probably always elude me.

The early version of the Lerner family that died was more complete, more full of promise, than the one that lived on, reformed itself. I’m haunted by this boy I never knew. By the parents and sister I never knew. And by the knowledge that my life is a kind of insult to his death. Nothing I ever do would make his loss worthwhile, of course, but I can’t help feeling that I should have lived in a way that did honor to him, a way that makes me deserve to be here instead of him.

All of this is one big unanswerable question. I can only say today, fifty years from your last day, Kenny… I’m sorry. And I wish you were here.

Wow! Incredible piece. Well I guess everybody is coming out of the woodwork to say they knew you when. I do remember you fondly. Our lives crossed paths in middle school, i think. Don’t remember why it never developed further. I always liked you and would have been glad to call you a friend. I guess our young immature selves didn’t know quite how to do it. Wishing you well, sally.

Oh my gosh, hi Sally! Yes it was definitely middle school… weren’t we in the same SWIS class together? With Ms. Newman and Chauvin? I remember walking w/you to your home in Lake Success after school. I don’t remember why we stopped being friends either, probably my fault. I was (and am) bad at keeping up relationships, kind of dropping off the face of the earth in hopes that the other person will chase after me. It’s a kind of test, like, if they follow up with me then maybe they really like me. But obviously no one likes to be tested like that. Also in high school I got more involved in theater and music, and I ended up chasing after that crowd myself. Another friend I had during high school whom I let slip away was Nadine Weidman–such a funny, unbelievably smart girl. Anyway I’m really sorry about losing contact with you, and I’m amazingly surprised and grateful that you read this post and got in touch. Hope you’ve been doing well…um, over the last 30 years! (Holy cow, how is that possible?!)

It’s hard to sum up 30 years but I’m doing well. One of the reasons I enjoyed your blog was because I’ve been emptying out the Great Neck house getting it ready for sale and that has brought up a lot of memories. Especially the high school years. It’s funny you mention Nadine because I recently reconnected with Melissa Mehlman on Facebook and she also asked if I had heard from her. Unfortunately, I was never friendly with her. Good luck with your writing and if you ever have free time when you are visiting Long Island, I would love to see you!.